From the Mouth of Resistance

What if one fine day your metaphors were snatched away from you and you were told that your art will be barred from reaching the world?

Dear you,

Dwell upon this, what if one fine day your metaphors were snatched away from you and you were told that your art will be barred from reaching the world? A huge part of our society belongs to the marginalized skies. Their voices are silenced and bashed at the gravel bottom. Their art comes with the grief they were attached to even before they were born. The umbilical cord of repression chooses to stay.

“Why didn’t an epic poet ever write a word about our lives?”

― Omprakash Valmiki

Voice, is a powerful weapon that scales our throats like a volatile knife. You get to feel the void and travel with them through the journey of how it takes so much resilience to speak when even the shadows of them were considered to be pollutants. The pit of endless struggles, the path laden with thorns, the glorious way to literature, in today’s abode we rest to you some of the unsung warriors, the ones who preserved art. The Dalit minority embodies the pinnacle of Indian literature's diverse land.

The Museum of Verses

1. Ontology of Our Language By Yogesh Maitreya

Naturally, when the placenta is cut The child is separated from mother However this isn't the case with us We are never separated from our mother Only those who fed on surplus Grow up, separated from mother We grow up inheriting the sound of her pain The sound which never reached the fate Of a language on paper Our handsome Bodhisattva taught us: Not talking to one’s mother is a horrible form of Alienation from our existence Therefore we understood: Mother tongue is essentially the sound We inherit when inside her abdomen Language is a just a suitable rendition Of that sound My grandfather had a hammer My father had the steering wheel I have a pen But we have been writing the same language The language of our mother Missing from the history of our existence.

2. My Sister’s Bible by S. Joseph, translated from Malayalam by K. Satchidanandan

These are what my sister’s Bible has: a ration-book come loose, a loan application form, a card from the cut-throat money-lender, the notices of feasts in the church and the temple, a photograph of my brother’s child, a paper that says how to knit a babycap, a hundred-rupee note, an S. S. L. C. Book. These are what my sister’s Bible doesn’t have: preface, the Old Testament and the New, maps, the red cover.

3. A Dalit Happy by Hsenura

When I have to write To all these publishing houses They ask me to write on pain Suffering, Hunger and Trauma And if I differ, they say These don’t look like Dalit poetry They can’t stand to read A Dalit Happy Either it should start with "We suffered in their hands" Or it should end with "Our hunger persisted forever" They said Their readers can't believe That a Dalit can be happy They said My poems aren't Dalit poems For they don't speak about oppression They don't speak about Ambedkar They don't speak about misery They said I'm a Dalit And so I must write hard hitting poems Poems that can revolutionize the world Poems that can disturb the privileged They said The market demands it But never said whose market it was They said A free dalit with upward mobility An independent dalit with confidence A romantic dalit with quest for love Can't exist in their books They said They need raw poems Associated more with soil With aesthetics and culture And when I said that we moved afar From those discriminatory native lands From the clutches of benevolent landlords They said, "go back to your roots" Yes I know My roots and culture Were stolen from my foreparents I know I need to write about it But should I never escape my trauma Should I not live in peace And write of all the beautiful things Like butterflies, rainbows and so on? And even when I write of animals They ask me to write on Pigs On buffalo, on native dogs, And all the other animals They won't associate with. They said a lot more What can I write on What can't I write on They trained me to be a Dalit poet They gained me the market My books to their stores And poems to their classrooms Which they include in syllabus The most mellowed of them all And pat themselves on their backs For being casteless and progressive Can I never write like them, About distant Casuarina trees? When their rare racism sighting is valid Why can't my rare happiness be valid too? When will my happiness be valid? When will my romance be valid? When will my peace be valid? When'd these be marketable? None of my trauma disturbs them None of my suffering disturbs them Only thing that always disturbs Every Oppressor's psyche Is the happiness of the Oppressed The success of them And the fearlessness of them Most importantly, their love.

मुख्यधारा एक जातीय वर्चस्व का प्रतीक है। जातिभेद संविधान ने हटाया, परंतु समाज में है, साहित्य में है। अम्बेडकरी साहित्य में लोकचेतना है। हिंदी पत्रिकाएं जाति स्वरूप की हैं। वह साहित्य में मुख्य भूमिका नहीं निभा रही हैं, फिर भी वह मुख्यधारा है। सत्यतः साहित्य की कोई मुख्यधारा किसी भी युग और किसी भी देश में वही हो सकती है, जो अधिक से अधिक पीड़ित, वंचित एवं संघर्षशील लोगों की अभिव्यक्ति का प्रतिनिधित्व करती है।

- श्यौराज सिंह बेचैन

श्यौराज सिंह बेचैन का लेखन हिंदी दलित साहित्यिक परिदृश्य में एक मील का पत्थर है। शोषण, गरीबी, अशिक्षा, जातिवाद और भेदभाव के शिकार दलितों के संघर्ष उनकी कहानियों के केंद्र में हैं। उनके कथा सृजन में उन शोषणकारी ताकतों की रूपरेखा तैयार की गई है जिनके परिणामस्वरूप दलितों को सामाजिक अधिकारों से वंचित किया गया और हाशिए पर रखा गया। आइए पढ़िए वर्तमान परिवेश को संदर्भ में रखकर दलित साहित्य के विषय पर श्यौराज सिंह बेचैन जी से की गयी युवा अध्येता उज्ज्वल शुक्ला और आँचल सिंह की बातचीत।

As we walk down the mundane lanes of chawls or urban spaces, we see faces; faces of those who are finding words to explain the unexplainable roads of their torn identities. Their trapped voices are locked and the keys are thrown deep under a mausoleum where returning peeps through the broken window of hope. Dalit literature must be widely lauded, for if fierceness had a face, it would be the forefront of all the faces who are aching to tell us a story, a story of their very existence. While you step into the lens of the world of Dalit art, your heart will ache, for it will fragment you to pieces hearing the realities. Time was barred to them, but what is time if not us dissecting our failed prayers in front of it? So they chose the pen and created an abode for us, a world far from here. The legacy of Dalit literature thrives in our hearts for it is a mark of poise. As Babasaheb Ambedkar said and I quote, “Cultivation of mind should be the ultimate aim of human existence.”

कविताओं की गली

1. आख़िर क्यों - असंगघोष

एक दिया मिट्टी का जलता था कभी-कभी भगवान के आगे उजियारा बिखेरता चमकते थे अपनी रहस्यमयी मुस्कान के साथ हाथों में नाना प्रकार के शस्त्रधरित भगवान मनुवाद को स्थापित करने युद्ध के लिए सदा तैयार दिखते, पर किसी भी रोशनी में कभी भी दिखाई नहीं दिए शिखाधारियों के षड्यंत्रों को रोकते दलितों पर होते दमन को थामते शस्त्रधारी पत्थरदिल भगवान।

2. कलम में खून - बाल गंगाधर ‘बाग़ी’

मैं लिखता हूँ तो कई बार रोता हूँ जब भी अछूत जिन्दगी को जीता हूँ दिमाग की नसों में घायल खून दौड़ता है जिसे अपने बाग़ी जख्मों से सींचता हूँ। नफरतों की आग में मेरे लोग जलते रहे अब जाति की जड़ी वो जंजीरें उखाड़ता हूँ शोले से जलते पिंजड़ों में कैद रहकर मैं सदियों से तड़पता समाज देखता हूँ स्याही ही जगह आंसू जब कलम में भरता हूँ बग़ावत की कलम से इतिहास को लिखता हूँ

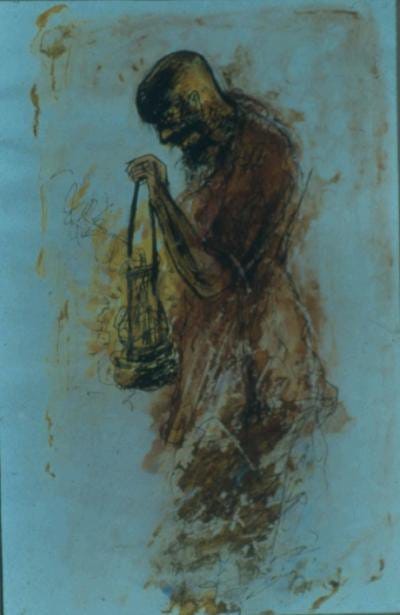

3. अंधेरे के विरुद्ध - दयानंद ‘बटोही’

अब मैं छटपटाता रहा हूँ तुम तो ख़ुश हो न? मेरी रौशनी दो, दो! मत दो? गहराने देता हूँ दर्द आख़िर रौशनी मेरी ही है न? तुमने कितनी सहजता से माँग लिया था आँखों की रौशनी को मैंने बिना हिचक दिया था ताकि तुम्हें कहीं परेशानी न हो न कुत्ते नोचें न कोई चोर-लबार सोचे अब नितरा-नितरा गाते हो गीत ओ दर्द देने वाले मीत तुम्हारी आँखें हैं पर पैर नहीं मेरे पास पैर हैं, पर आँखें नहीं बहुतों को मैंने पार किया है अपने कन्धे पर आओ तुम भी मेरे कन्धे पर बैठ जाओ तुम रास्ता बतलाओ न! नहीं बताओगे? मैं तो लहूलुहान ज़ख्म पालूँगा और तुम! पर वाले हो जाओगे क्योंकि तुम मेरे कन्धे पर रहोगे मेरी आँखों की रौशनी को तुमने जलाकर छितरा दिया सिर्फ़ बचा रह गया गट्ठर ढोने वाला कन्धा मेरा कन्धा दुःख जाएगा जब महसूस करने लगूँगा रास्ता बताओ, नहीं बताओगे? तुम्हें बीच नदी में भी गिरा सकता हूँ जहाँ बहती है आग की नदी मुझे रौशनी दो तुम्हीं ने छीन ली थी बार-बार मेरी आँखों की ज्योति।

4. जाति - ओमप्रकाश वाल्मीकि

मैने भी देखे हैं यहाँ हर रोज़ अलग-अलग चेहरे रंग-रूप में अलग बोली-बानी में अलग नहीं पहचानी जा सकती उनकी 'जाति' बिना पूछे मैदान में होगा जब जलसा आदमी से जुड़कर आदमी जुटेगी भीड़ तब कौन बता पाएगा भीड़ की 'जाति' भीड़ की जाति पूछना वैसा ही है जैसे नदी के बहाव को रोकना समन्दर में जाने से!!

The map of Dalit literature is often side-lined and kept on as the rocks in the mountains where each layer of the rock is made of grief and rage that is tattooed on your back. Have you ever witnessed mothers scolding their kids and saying, “if you do not study now, you will end up being a domestic worker we have in our home”? Pause for a moment, and think about the different socially marginalized backgrounds they hail from and how the very comparison is wrong in every aspect. But this is how the normalization of the narrative in the hegemonic caste works. You have to dive deep into the pit of the caste system to engage with the discourses in India. Dalit literature is a safe space where you discern the abandonment, discarding existence, misery, a war with the society, and a war of identity. As I read somewhere, the day Dalit hope ends, the state’s hope for Dalits will end. This end is to the peril of the Indian state and all who cohabit in it. Literary activism during the Dalit Panther era has been soaring high ever since. Dalit literature not only talks about their suffering, but also of Dalit hope, Dalit love, and the voices of the sufferers.

“On her neck, she wears not the thaali, that marker of marriage, but a cyanide capsule. She embraces not men but her weapons”- Meena Kandasamy

Meena Kandasamy's pen doesn't wear a veil of decorum as it inks The Gypsy Goddess. She doesn't have time for it. She has to tell a story. She doesn't shy away from quoting the exact details of the wounds found on the bodies of all 42 (+2 silent) corpses. The pen sometimes assumes a screeching staccato, like shards and heartbeats, and sometimes spirals into long sentences, winding, convoluting, lost like some people in the story.

कक्षा में पढ़ाया जाता था कि बच्चे ईश्वर द्वारा निर्मित फूल हैं। तो क्या हम भगवान् द्वारा निर्मित फूल नहीं हैं? वास्तव में, हम लोग गाँव के बाहर फेंके गए कूड़े-कचरे की तरह थे। एक ही स्कूल में अनेक जाति की इकाइयाँ थीं। हमारी बस्ती का सम्बन्ध गाँव से नहीं था; मानो गाँव का विभाजन कर हमें गाँव से तोड़ा गया हो। बचपन से मैं पराये की तरह ही रहा। उम्र के साथ यह परायापन बढ़ता ही गया था। मेरा बचपन मुझे आज भी भयावह लगता है।”

- शरणकुमार लिंबाले

भोगे हुए यथार्थ के दुःख की नींव में हमेशा एक चिंगारी होती है। यह चिंगारी दो मुही है, जो अगर अभिव्यक्त न हो पाए तो भीतर ही भीतर पीड़ित को भस्म कर देती है और यदि अपनी उचित दिशा पा जाए तो सृजन का रूप ले लेती है। ‘अक्करमाशी’ उसी सृजन की उपज है। एक सहा गया विद्रूप जीवन, जिसकी वीभत्स शैली ने लिंबाले को मराठी भाषा के प्रतिनिधि दलित लेखक की दहलीज़ पर लाकर खड़ा कर दिया।

‘अक्करमाशी’ एक मराठी शब्द, जिसका अर्थ है - एक ऐसी संतान जिसके माता पिता पारम्परिक ढंग से विवाह सूत्र में न बंधे हों, अर्थात नाजायज़ संतान। लिंबाले को इसी शब्द के संग दुनिया की दुनियादारी में समाज द्वारा दर्जा दिलाया गया था। उपन्यास के प्रारम्भ में हम देखते हैं कैसे लेखक महाराष्ट्र - कर्नाटक की सीमा पर स्थित गाँव की दलित बस्ती में अपना बचपन गुज़ार रहा है। शुरुआत से ही किशोर शरण अपने मन में कई जटिल प्रश्नों को लिए आगे बढ़ता है। एक मासूम बच्चे को जिसे यह भी नही मालूम कि उसका असल पिता कौन है, गंदगी से भरे मानसिक एवं भौगौलिक परिवेश में निर्वाह करते देख, मन एक असहायता से भर उठता है। किस तरह एक दलित किशोर अपनी असल पहचान की तलाश में झूझ रहा है, यह एक बने बनाए सामाजिक ढाँचे पर कड़ा प्रहार करता है।

This issue of our Newsletter comes to a close, but we've curated more pieces of writing from Dalit Literature and will continue to share them on our social media under the hashtag #FromTheMouthOfResistance.

Thank you so much for taking the time to read this. If you enjoy this newsletter, please consider dropping a comment, sharing it with a friend, or becoming our patron.

Contributors: Prasangana Paul, Aishwarya Roy, Devansh Dixit, Ujjwal Shukla, Aanchal Singh, Shivam Tomar

This was extremely wonderful, such beautiful things to read. Thank you for bringing this to us!

In a world, where every platform is practicing tokenism to be progressive, without any intent to do something to resurrect muffled voices, efforts such as this by Poems India should be read and shared as much as we can. Thank you for this, Dil Se :)