On Reading Banu Mushtaq

Nishant Kaushik on reading Heart Lamp and the deeper resonance of these seemingly familiar stories.

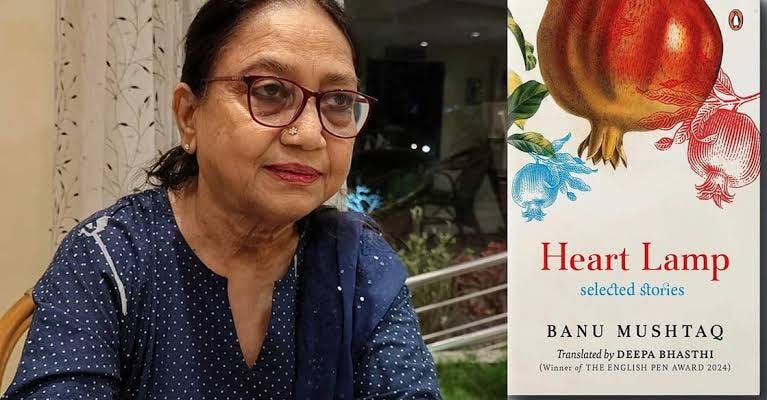

I have Banu Mushtaq’s Heart Lamp in my hands. It is a collection of twelve stories translated deftly by Deepa Bhasthi from Kannada to English. The book’s triumph in the International Booker Prize a couple of days ago is a source of great satisfaction for the entire Indian literary landscape.

This book features a curated selection of 12 stories from Banu’s many published across a range of collections. While readers have both praised and typecast the compilation as representative of South Indian Muslim society, this characterisation, though accurate, fails to capture the complete range of Banu's literary prowess. While these stories explore transitional phase where male-female relationships undergo troubled evolution, many readers may still find them lacking in novelty as the plot structures remain familiar and the atmosphere feels stale, despite the altered geographical settings. Banu states that these stories emerged from her lived and witnessed experiences. She is an activist and a lawyer and many of her characters are drawn from the world around her. If readers feel that the subject matters in these stories have already been exhaustively used, it doesn’t represent an artistic failure. Instead, it’s a social tragedy that Inequality is so deeply entrenched that we need fiction to perceive what surrounds us in everyday life.

Besides this, the stories are full of all kinds of substance that compels me as a reader who ends up writing this piece.

The majority of the stories like Stone Slabs for Shaista Mahal, High-heeled shoe, Be a woman once, Oh Lord!, Fire-rain and the titular Heart Lamp deal with the subjects of societal disparity and adaptation. Reserved, unseen, unnamed and overlooked characters are the heroines of these stories. This may not be the most prominent aspect of the stories, nor is it suggested that such characters haven’t appeared elsewhere. Yet, the social function they serve here remains compelling and worthy of attention.

In the story Fire Rain, the antagonist Mutawalli is irritated by his sister’s demand for a share in the family property. In an attempt to avoid confronting this domestic conflict, he immerses himself in leading a communal issue. He devotes all his energy to spotlighting a communal incident, and other family members, including his sister, join in with veiled complicity. However when the situation backfires, the very questions of property division and household responsibility that Mutawalli was trying to escape resurface.

This is a powerful story about gendered access to social roles, showing how men often redirect attention to seemingly noble public causes as a way of evading uncomfortable personal inequities. It also reveals how conflicts tied to religious identity can be carefully constructed, and how they often remain separate from the broader and more pressing struggles against everyday injustice.

In these stories, men are almost entirely absent from crucial and confrontational conversations, such as those related to divorce, remarriage, household decisions, or safety concerns. In the story Heart Lamp, Mehroon, who has returned to her parental home, is taken back to her husband’s house by her brothers-in-law, who then begin talking among themselves over coffee about the Kashmir elections and a murder that took place in the neighborhood. In Fire rain, Mutawalli (the antagonist) is a Pascalian kind who would rather wage a war than pay heed to the demands of rights and equality. In Stone Slab for Shaista Mahal, similar conversation continues.

A pervasive sense of entitlement in all the stories infringes upon the right of others to choose their own happiness and freedom. In Stone Slab for Shaista Mahal and High Heeled Shoe, the male characters search for their own version of a blissful paradise for their wives - whether it's building a Taj Mahal or nurturing an eternal dream of making their wife wear high heeled shoes. I am compelled to quote a line from a poem by Journalist-poet Priyanka Dubey which to some extent capture this dynamic:

“Mere liye Chand todkar mat lao, mujhe jane do”

which roughly translates to

“Don’t fetch the moon for me, just let me go.”

In the development of characters, notable shifts emerge in stories like Heart Lamp and Stone Slabs for Shaista Mahal. Female characters find themselves being pushed into the same exploitative world from which they are attempting to escape by their mothers and sisters. In contrast, the daughters of these women sometimes take on the roles of protectors, rescuing their mothers from dire situations such as preventing them from burning themselves with kerosene. Such are the protagonists like Mahroon and Shaista.

The Arabic Teacher and Gobhi Manchuri is easily the most intriguing story in the book, mostly because its characters are so strange. A teacher is appointed to teach Arabic and the Quran to two girls in a household. He does his job well. There are no complaints about his teaching. But he has an odd obsession with a dish he calls Gobhi Manchuri. He is always thinking about it, cooking it, eating it. The story never quite says whether this is the same as the popular Manchurian or something else entirely. One day, he is caught in the kitchen making Gobhi Manchuri with the children. After that, he flees the house and never returns. Only his stories remain in the household. The lawyer-mother keeps hearing them- that how he insisted on marrying only a woman who could cook Gobhi Manchuri. That he beat his wife when she could not. Eventually, his case comes to the lawyer’s (mother of those two kids) desk. She finds herself holding his file in one hand and a recipe for Gobhi Manchuri in the other.

This story explores how violence becomes normalized alongside the seemingly innocent nature of obsession. This obsession with making and eating Gobhi Manchuri initially appears strange, then seems innocent and harmless, but ultimately reveals itself as both violent and compulsive. Yet it presents itself to the lawyer without disturbing her, as she simultaneously observes the recipe and the account of violence side by side. The story is satirical in its treatment of this subject. These ironic touches are scattered throughout Banu Mushtaq's stories. Despite their stark and serious plotlines, this satirical quality is a commendable feature of these stories.

Banu Mushtaq’s stories often feel like they happen nowhere in particular. There is a strong sense of local life in the way people speak and relate to each other. Villages near Mysore are mentioned and characters move between rural areas but cities or specific places never take on a strong presence in the story. The usual contrast between city and village that we often see in South Asian fiction is mostly missing here. Calling these stories ‘South Indian Muslim’ fiction also feels a bit limiting. It seems based more on the writer’s identity than on what the stories actually explore. The Muslim families in these stories are like any other subcontinental household. With small changes in customs or religious details, they could easily be any ordinary family, with all their everyday struggles and contradictions. It’s possible that the original Kannada version carries more of a sense of place through the language, which may get lost in translation.

The book has been translated from Kannada to English by Deepa Bhasti. The target language of a translation can give both the book and its author a new shape, a new world. In the past ten to twelve years, we’ve seen excellent English translations of Indian languages. These translations show a serious kind of consistency and dedication, with the goal of doing justice to the original. We have moved past a whole phase of non-professional translation. This shift is both important and welcome.

Speaking about Kannada translation, Deepa Bhasti has pointed out that in multilingual India, not every language or way of speaking has to point to political or social issues. She notes that certain sounds from Urdu, Persian, or Arabic (common in the north) are often dropped in Dakhni. For eg, the sound ‘Q’ in ‘Qabristan’ becomes ‘K’ in ‘Khabristan’.

While translating idioms and forms of address, she has also kept in mind how Indian families use or avoid names when calling or introducing someone and how that changes the tone. Repetition in verbs, which is very common in conversation, has been kept in the English version just as it is in Kannada.

For readers like me, this translation feels easy to read and understand. It should be appreciated not just as a piece of fiction, but also for the way it handles translation.