The Benegal Blueprint

Shyam Benegal showed that with the right strategy, artistic integrity and commercial success need not be mutually exclusive.

Good films are like garlic—they have a taste and a stronger, long-lasting aftertaste. This rings especially true for Shyam Benegal's works, which linger long after the credits roll. But what distinguished Benegal from his predecessors was his innovative approach to overcoming the traditional challenges that had long plagued India's New Wave cinema movement. With his passing, we have lost not only a visionary director but a true innovator who transformed Indian cinema.

Parallel cinema in India faced numerous barriers that limited its reach and influence. From the 1940s to the early 1970s, filmmakers in this movement struggled with distribution problems, financial constraints, and limited audience appeal. Even celebrated directors like Satyajit Ray found it difficult to secure funding, while Ritwik Ghatak's films, though powerful, often struggled to find distributors. Consequently, most of parallel cinema remained confined to urban intellectual circles, unable to connect with broader audiences.

These challenges had historical roots. Since Raja Harishchandra (1931), Indian cinema had developed along two distinct paths: mainstream commercial films and parallel cinema. While commercial cinema flourished with its mix of mythology, music, and melodrama, parallel cinema struggled to find its footing despite producing socially conscious works. The Bombay Progressive Film Movement of the 1940s, led by filmmakers like Khwaja Ahmad Abbas and Chetan Anand, focused on class struggles and social justice, but these films often failed to reach a wide audience or achieve commercial success.

Benegal's brilliance lay in addressing these issues head-on. To tackle the perpetual funding problem, he developed innovative financing models. His film Manthan (1976), which explored the white revolution in India's dairy industry, pioneered crowdfunding in Indian cinema, being financed by 500,000 dairy farmers who contributed two rupees each. This revolutionary funding approach not only solved the financial challenge but also created an invested audience base—the farmers who funded the film became its first viewers and promoters.

Distribution, another critical hurdle for earlier filmmakers, was addressed by Benegal through a blend of high production values and intelligent storytelling. His 1983 film Mandi, a satirical take on politics and prostitution, based on an Urdu short story written by Ghulam Abbas, demonstrated this approach perfectly—it tackled a controversial subject with such technical finesse and artistic merit that distributors couldn't ignore its commercial potential.

Benegal's mastery of diverse subjects while maintaining commercial viability was evident in films like Zubeidaa (2001), based on a true story about a Muslim princess who became an actress. The film, starring Karisma Kapoor, represented Benegal's ability to work with mainstream stars while telling complex, layered stories. Similarly, The Making of the Mahatma (1996), a joint Indo-South African production about Gandhi's early years, showed how he could handle international co-productions while staying true to his unique vision.

A key departure from previous filmmakers was Benegal's casting strategy. Unlike his predecessors who often relied on non-professional actors, he worked with established talent like Shabana Azmi, Naseeruddin Shah, and Smita Patil. His film Bhumika (1977), inspired by the life of Marathi actress Hansa Wadkar, earned Smita Patil national acclaim and demonstrated how star power could be harnessed for serious cinema. In Trikal (1985), set in Portuguese Goa, he expertly wove together a large ensemble cast to create a complex narrative about family, politics, and social change.

This approach created what became known as "middle cinema"—a sweet spot between artistic integrity and commercial viability. Films like Ankur (1974), which marked the debut of both Shabana Azmi and Anant Nag, proved that serious social commentary could coexist with accessible storytelling. Benegal's Susman (1987), exploring the lives of handloom weavers in Andhra Pradesh, maintained this balance while addressing economic exploitation and cultural preservation.

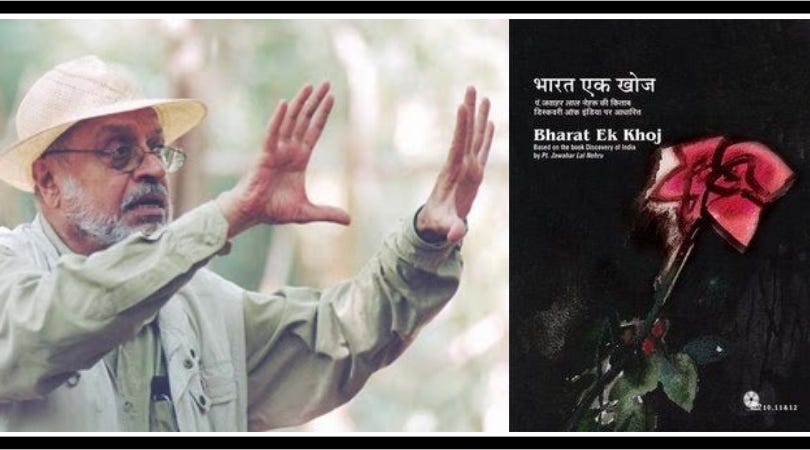

His television work also broke new ground. The serial Bharat Ek Khoj (1988), based on Jawaharlal Nehru's "Discovery of India," set new standards for historical storytelling on Indian television, proving that quality content could work across mediums. This success in television further strengthened his position with film distributors and financiers.

The success of Benegal's model influenced both parallel and mainstream cinema. His film Samar (1999), which explored caste dynamics through a meta-narrative about a film crew documenting caste violence, demonstrated how complex social issues could be approached in innovative ways. Sardari Begum (1996), telling the story of a classical singer through multiple narratives, showed how traditional storytelling could be reimagined for modern audiences.

The challenges that had constrained earlier New Wave directors became opportunities for innovation in Benegal's hands. By systematically addressing each obstacle with creative solutions, he not only succeeded as an individual filmmaker but also created sustainable pathways for future generations of directors wanting to make meaningful, socially conscious cinema without sacrificing commercial viability. His diverse filmography, spanning over four decades, stands as testimony to the success of his approach—proving that with the right strategy, artistic integrity and commercial success need not be mutually exclusive.

With Shyam Benegal's passing, Indian cinema has lost a master architect of its cultural landscape. Benegal cultivated a space where art and commerce could coexist, allowing the roots of meaningful storytelling to grow deep while reaching wide into the mainstream. Though his hands are no longer shaping the frame, the shadows of his work will stretch across generations.

This post is written by Shivam