The Many Lives of the Mango

The mango has seen civilizations rise and fall, from prehistoric forests to royal gardens to the plastic crates as you must have seen in your local market.

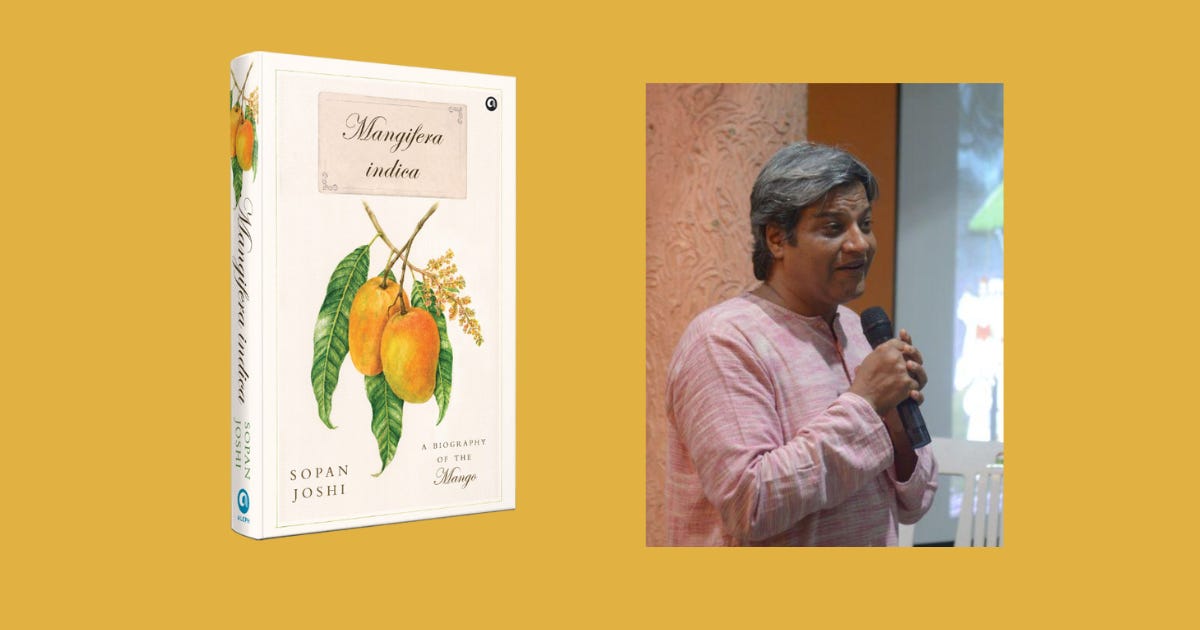

Reading Mangifera Indica: A Biography of the Mango by Sopan Joshi feels like sitting under a mango tree with a friend who knows everything about the fruit and can’t wait to tell you. It’s not just a book about mangoes; it’s a love letter to the fruit that’s been part of our lives forever, from childhood summers to market trips. The author digs into the mango’s story, blending his own memories with history, culture, and the gritty realities of what goes on inside mango orchards and markets. It made me rethink what I thought I knew about mangoes, and I bet it’ll do the same for you.

The book offers a bold claim that we think we know mangoes, but we don’t. And as you read along, the claim becomes evident. The mango has seen civilizations rise and fall, from prehistoric forests to royal gardens to the plastic crates as you must have seen in your local market. It’s a humbling idea, and the author doesn’t lecture you about it. Instead, he invites you into his world, sharing memories of his own mango-filled summers and charming anecdotes, like the time he heard about traders getting desperate calls for Alphonsos to fulfill someone’s dying wish. It’s like he’s sitting across from you, peeling a Totapuri and telling stories.

The book is split into three parts, each one a different lens on the mango. In the first part, we see why mangoes are so special to us. We get to know how the fibers of mangoes are intertwined with those of our society. And why nobody says no to a box of mangoes, whether it’s a gift or a sly bribe that won’t get you in trouble.

There's a great bit about the Delhi-Mumbai rivalry over Dussehri versus Alphonso. The socio-political activist Rajan Prasad claims that Mumbai cannot be called a city because it lacks the two basic qualifications for a serious claim to urban culture: a poet like Mirza Ghalib and a mango variety like Dussehri. Meanwhile, Anand Desai, the mango trader from Maharashtra, claims, "Nobody who can afford the Hapus eats anything else in the season." Then comes the retort where Northerners claim that you never have to apologize for a ripe Dussehri, unlike an Alphonso, which sometimes shows up underwhelming and overhyped. And this goes on; there is no end to the Alphonso-Dussehri rivalry.

Sopan Joshi also sprinkles in stories from his travels across India, where he talked to farmers, traders, and everyday folks. One of them is about Mahatma Gandhi, who planted a mango seed while in Yerwada Jail. When he was released, he took the sapling with him, and since he vowed not to return home until India was free, that sapling somehow ended up at Sarojini Naidu’s house in Hyderabad. It’s now a full-grown tree. Stories like this make the book feel personal, like the mango is part of our shared history.

The historical part of the book is where things get wild. It takes us back to the time after the dinosaurs, explaining how early primates evolved color vision and flexible shoulders- adaptations that helped them spot and pick fruits like mangoes. It’s crazy to think our love for mangoes is wired into our biology. He also mentions an archaeological find in Farmana, Haryana, where 4,500-year-old grinding stones had traces of mango in brinjal curries. We’ve been cooking with this fruit longer than we’ve been writing about it.

Then there’s the cultural stuff. Joshi points out how mango leaves are used in Hindu rituals, like on mandaps or in the Purnakalash, in which five mango leaves are placed around the mouth of the pot, each symbolizing one of the five elements, i.e., panchatatva. "There’s a Buddhist story in which the Buddha saw two mango trees: one full of fruit but stripped of leaves, as people stood beneath it constantly throwing stones; the other lush with leaves but fruitless, standing undisturbed in its serenity. This vision became a lesson on the importance of letting go of possessions. These bits show how the mango isn’t just food; it’s part of our myths and beliefs.

The modern name bearing down upon mango writing is the nineteenth-century poet Mirza Ghalib. In perhaps the most famous modern couplet on the mango, he speculates on the fall of Adam from Eden after consuming the forbidden fruit of knowledge, which in Islamic canon is gandum, or wheat. Ghalib questions Adam's choice of fruit:

Firdaus mein gandum ke evaz aam jo khate

Aadam kabhi jannat se nikaale nahi jate

(If he had eaten the mango instead of wheat

Adam wouldn't have been evicted from Paradise)

In the last part of the book, Joshi gives each region its due by telling stories of its special mango varieties. We get to know about Banganapalle, Imam Pasand, Chinnarasalu, Swagatham, Neelum, Totapuri, and Shakkar Guthli from the South. Alphonso/Hapus, Makurad, Noorjahan, and Kesar from the center and west. Langda, Rataul, Dussehri, Gandharaj, Kapooriya, and Chausa from the North. And from the East, we get Kohitoor, Zardalu, Rani Pasand, Kalapahar, and Malda.

The author traveled to orchards all over India, from Murshidabad to Banganapalle, to learn about varieties I’d never heard of. Take the Noorjahan mango from the Madhya Pradesh-Gujarat border-it can weigh three kilos and cost ₹1,000 a piece. Or the Kohitoor from Murshidabad, so fragile it’s packed in cotton to keep its flavor intact. Then there’s the Banganapalle, called Benishan in Andhra, Safeda up north, and Badam in the west. Joshi describes cutting one open, the juice running down your arm, and the skin peeling off like butter paper. I could almost taste it.

He also dives into the science and business of mangoes. Did you know commercial mango pulp is 90% Totapuri and 10% Alphonso because Totapuri fruits every year, while most others skip years? Or that Alphonso’s famous taste comes from a sugar-acid balance that’s sweeter the closer the orchard is to the sea? These details stuck with me, making every mango I buy feel like a little mystery: where did it come from, and what shaped its flavor?

It's not all glorification and anecdotes. The book addresses the challenges that current generations of mango growers and traders face, giving due attention to problems like biennial bearing (when trees only fruit every other year) or mango anthracnose, a fungal disease that can devastate and ultimately kill a tree. Joshi explains how irrigation developments in the Godavari region significantly boosted production but simultaneously introduced new pest problems and how excessive pesticide use not only kills essential pollinators but also creates increasingly resistant insect populations.

The author also provides a fascinating glimpse into the lives of a Malihabadi colony, where all the inhabitants work at mango orchards as seasonal laborers for three months during the harvest season, while for the remaining nine months of the year, they return to their traditional livelihoods in the evergreen crafts of zardozi embroidery and chikankari needlework to sustain themselves.

While the book seems to uncover all there is to mangoes, Joshi admits he hit language barriers in places like Banganapalle, where he couldn't fully connect with local growers. Despite this limitation, the book evoked memories of my village summers, when mangoes represented adventure rather than mere fruit. I recall aiming gulels (slingshots) at raw mangoes, feeling like Arjuna from the Mahabharata. Last summer, I recognized that same spark of joy as I watched my nephew climb a mango tree at our ancestral home, his face puckering from biting into sour fruit.

The book also illuminates mangoes' cultural significance, from the 2007 "Mango Deal" with the US (trading Harley-Davidson access for Alphonso exports) to the poignant story of Hijron ki Amrai in Narsinghpur, a mango grove gifted to the transgender community after they were denied access to a Hindu cremation ground. These narratives reveal how mangoes have become vessels carrying our humanity in all its complexity.

Mangifera Indica: A Biography of the Mango by Sopan Joshi is for anyone who’s ever loved a mango or wondered about the stories behind everyday things. Joshi turns a fruit we take for granted into a window into India’s past, present, and future. If you want to laugh, learn, and maybe rethink your next market trip, this book’s for you. I’m already planning to go searching for a Noorjahan in the coming week, and I bet you’ll want to, too.

Written by Shivam

In case you want to read the book, here is the link to purchase it.